For what may be obvious reasons, I recently read every story in the original Sherlock Holmes canon — all four novels and 56 short stories.

(This is not bragging. 56 is not that many. Harlan Ellison, one of my favourite writers, is said to have written over 1 000 short stories in his lifetime. You’re welcome to try and verify that claim, but you’ll probably get distracted by the “Controversies and disputes” section of his Wikipedia page.)

The Holmes stories were written before we as a culture fell from god’s grace and invented sequel hooks. As a result, I was struck by the fact that some of the canon’s most famous characters appear quite suddenly and don’t stick around for very long.

An example: if you asked the average person to name three Sherlock Holmes characters, they’d probably say “Holmes, Watson, and Moriarty.” But Professor Moriarty only factors into two stories, and personally appears in just one: “The Final Problem,” in which he pops up out of nowhere to kill Holmes. The second story, The Valley of Fear, takes place before “The Final Problem” but was published 21 years later, establishing Moriarty as a recurring threat well after the fact.

Another example: if you asked the average person to name three Sherlock Holmes characters, but stipulated at least one of them had to be a woman, they might say “Holmes, Watson, and Irene Adler.” Because Adler is the Woman — the woman who bested Sherlock Holmes.

Within the canon — specifically, the short story “A Scandal in Bohemia” — the facts of Irene Adler are these:

- She was American, born in New Jersey.

- She was once an opera singer who performed in Milan and Warsaw. She’d mostly retired by the time of “Scandal” and moved to London, where she sang at concerts and otherwise “live[d] quietly.”

- Five years before the events of “Scandal,” she had an affair with the Crown Prince of Bohemia. They exchanged “compromising” letters and had a photograph taken together.

- After the prince was crowned King of Bohemia and became engaged to a fellow noble, he claims Adler threatened to expose the affair. This may or may not be true; Adler later claims in a letter to Holmes that she kept the photograph “only to safeguard myself, and to preserve a weapon which will always secure me from any steps which [the king] might take in the future.”

- She then resisted all attempts by the king to buy and/or steal the photograph from her, at which point he hired Holmes to acquire it for him.

- She was more than a bit altruistic; when a disguised Holmes faked an injury, she hesitated only briefly to allow him into her house for care. Watson, in particular, “never felt more heartily ashamed of myself in my life than when I saw the beautiful creature against whom I was conspiring, or the grace and kindliness with which she waited upon the injured man.”

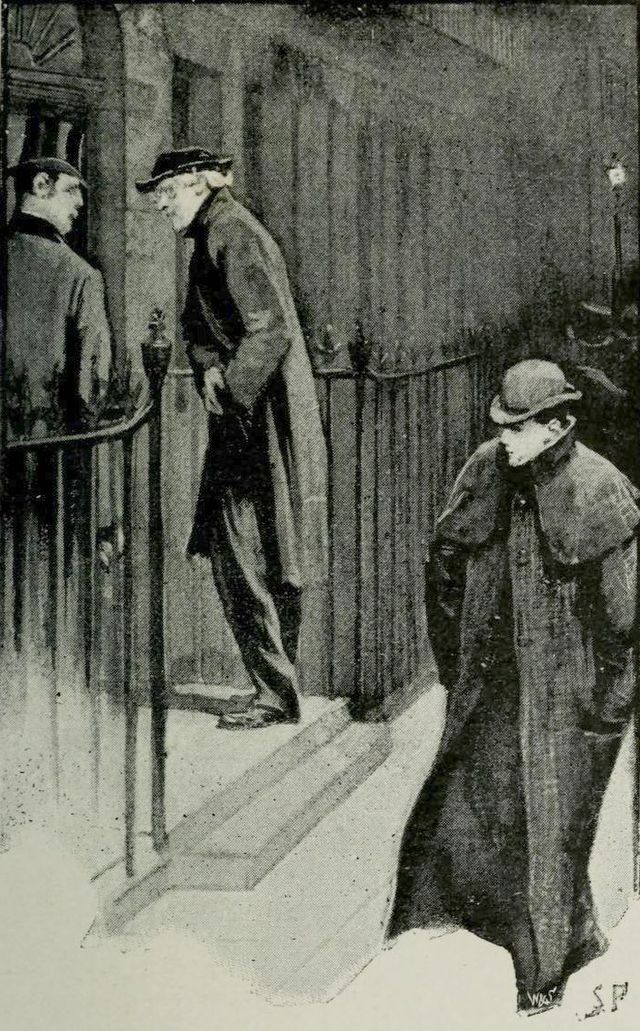

- After Holmes used a false fire alarm to determine the photograph’s hiding spot, Adler was clever enough to realize what had happened. She disguised herself in men’s clothes, followed Holmes and Watson home, and eavesdropped on their plans to steal the photograph. She then skipped town, taking the photograph with her.

- She was not, notably, romantically entangled with Holmes. Holmes didn’t feel “any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler.” Adler, meanwhile, had a husband — Godfrey Norton — who she at least claimed to have married for love. Holmes, in disguise, served as the witness at their wedding.

Adler never appears in any other Sherlock Holmes story. In fact, within the first paragraph of “Scandal,” it’s a foregone conclusion that she has since died: “the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.”

And yet within the last few years, whenever Sherlock Holmes shows up on screen, some version of Irene Adler usually follows:

- In the movie Sherlock Holmes (2009), Adler is an itinerant con artist who’s implied to have married and left multiple men; she’s also a former flame of Holmes’ who swans back into his life like a noir femme fatale to kick off the movie’s plot.

- In the TV series Sherlock, Irene Adler is a professional domme who uses incriminating photos and videos to blackmail her clients — one of whom is a member of the royal family. She’s also a lesbian (interesting) who is, nevertheless, in love with Holmes (less interesting).

- In the TV series Elementary, Irene Adler is an art restorer, occasional thief, and girlfriend to Holmes who was apparently murdered before the events of the show. She later reappears, alive, and is revealed to be a false identity created by Jamie Moriarty (Elementary’s version of Holmes’ nemesis).

These are fairly dramatic departures from the character described in “Scandal.” But it’s been well over a hundred years since “Scandal” was written — surely these versions of Adler represent a modern, more feminist perspective, right?

Well …

Sherlock’s Adler is bested by Holmes, specifically because she’s in love and obsessed with him. The Adler of Sherlock Holmes (2009) and its sequel is, ultimately, a pawn in the game between Holmes and Moriarty who is imperiled and eventually killed to motivate Holmes. Elementary’s Adler is, depending on where you are in the show, either a fridged girlfriend or nonexistent.

All these takes on Adler don’t make for a more empowered female character. Instead, they reflect a desire from their creators to punch her up — to make her more worthy of her title as “the woman who bested Sherlock Holmes.”

Because in most screen adaptations, Sherlock Holmes is portrayed as a superhuman intellect. In some of them, like Sherlock, he might as well be psychic. And if Holmes is a superlative genius, then anyone who outsmarts him must be special in some way — a master manipulator who befuddles him with her sexuality, or a criminal mastermind on the same level as his literal nemesis, or some combination of the two.

But what makes the Irene Adler of “Scandal” exceptional is how unexceptional she really is.

Throughout the Sherlock Holmes canon, Holmes is insistent that his methods don’t rely on superhuman prescience — simply on, as he says in The Sign of Four, a combination of knowledge, observation, and deduction. Anyone who possesses these three qualities could do what he does.

Anyone at all — like Irene Adler, for instance. She knows (thanks to a hot tip from an unnamed party) that the king will hire Holmes to steal the photograph, and looks into who he is and how he operates. She observes that Holmes in disguise isn’t what he seems and surveils him to learn more. And she quickly deduces that she’s about to be robbed — at which point she takes the photograph and just leaves.

She’s not a criminal genius or a femme fatale. She’s not smart “for a woman”; she’s just a smart woman. Holmes’ failure to outwit her wasn’t because she seduced or manipulated him — it was because he underestimated her. He thought she was inferior, and therefore assumed he could anticipate her every move.

But she wasn’t, so he couldn’t.

And that’s why she’s the Woman.

Leave a Reply