And finally, this work is also dedicated in furious disgust to ridding our world of the influence of everyone complicit in using the pandemic as a tool for their own power, profits, and political maneuvering. You pushed hateful agendas while the bodies were stacked up. We all lost people dear to our hearts because of you parasitic, heartless creatures. If you had souls, you’d be damned.

from the dedication of Beyond, by Mercedes Lackey.

I think it’s safe to say Mercedes Lackey is sick of this shit.

This summer, I started rereading the Valdemar books. This wasn’t prompted by the recent announcement that a television series is being made; I was just one of many hit with Apollo’s big rubber dodgeball of prophecy this year. I can’t really say what brought on my impulse to revisit the series. Maybe the fact that I had just moved to a new country to start a new job inspired a need to latch onto something familiar.

I first started reading the Valdemar books as a young teenager. I came across a copy of The White Gryphon on a thrift store bookshelf and was immediately attracted by three things on the cover:

- A lavishly-detailed painting of a gryphon,

- A title in purple stamped foil,

- A $2 price tag.

Needless to say, I was hooked.

The first time around, I stalled out on the series about halfway through the Mage Storms trilogy. This summer, I’ve made it all the way to the Valdemar books published this year.

Rereading Valdemar as an adult, I started to pick up on things I’d missed as a kid. Where most secondary-world fantasy is set in Fantasy England (or, if you’re a relatively imaginative author, Fantasy Eastern Europe), Valdemar is very much Fantasy America. And I do mean fantasy. Valdemar is the America that Emma Lazarus was talking about when she wrote “Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Valdemar is a nation of refugees and a nation of refuge. A society that’s as close to egalitarian as a late-medieval, early-renaissance setting can get. A place where the only overriding principle is “there is no one true way.” Over the years, Valdemar has featured prominent female protagonists, heroic queer characters, sympathetic allegories of indigenous people, mental illness and neurodivergence, and most recently asexual and trans characters. The handling of these topics is frequently indelicate and/or outdated—many of the books were written in the 80s and 90s and Lackey is, at time of writing, 71 years old—but clearly comes from a strong authorial belief that the differences between people should not just be tolerated, but celebrated.

The early books are very much rooted in Cold War naivete, depicting Valdemar as a bastion of freedom against relentless enemies. After the Berlin Wall came down, the books took on a more subtle dimension—former enemies become allies, and disparate lands began to unite against an oncoming natural disaster. The Mage Storms trilogy in particular feels very much like “the end of history,” with the subsequent trilogy Darian’s Tale feeling almost like a coda or an epilogue. It’s no surprise that all the Valdemar books afterward were prequels.

The Valdemar books of the late 2000s and 2010s start to reflect a growing post-9/11, post-War on Terror understanding that “freedom” spread by the sword is no freedom at all. And starting in 2016, with Closer to the Chest, the culture war arrives in Valdemar; the whole novel is about incel culture and cyberbullying. 2019’s Eye Spy follows that up with a sexist, rich-boy villain named “Dudley Remp,” who’s described as having “unusually small hands.”

Lackey has never been a particularly subtle writer, but you can see her getting angrier and angrier with every book.

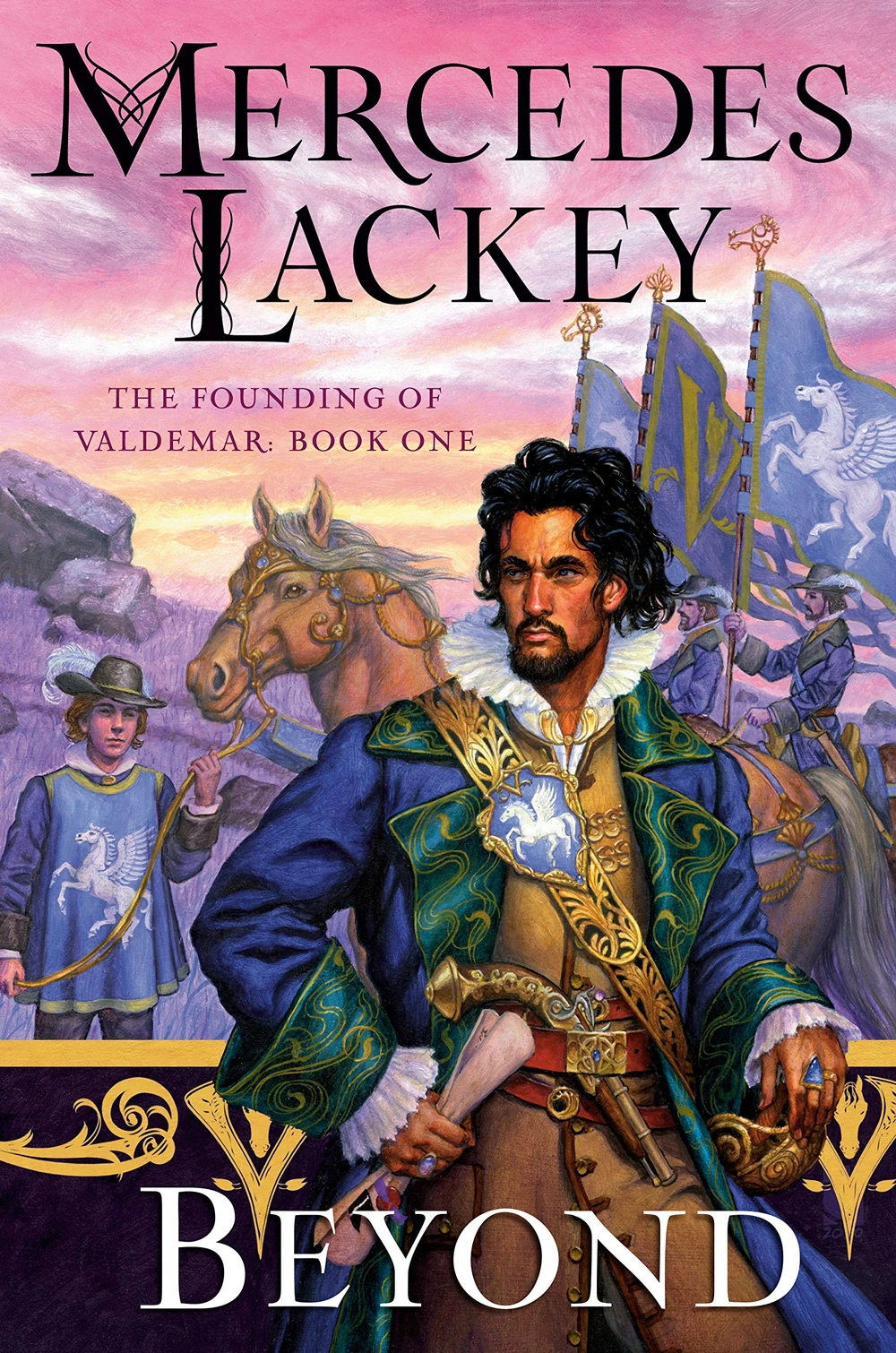

And that brings us to Beyond, published this year as the first book of the Founding of Valdemar trilogy.

In previous books, the founding of Valdemar has been depicted in the style of an American History class taught to 10-year-olds: Baron Valdemar fled an oppressive Empire and started his own kingdom where freedom and equality would reign. In Beyond, we don’t just see the ideals he’s working toward—we see what he was running from.

And if Valdemar is the fantasy of what America could be, then the Empire is the America that Lackey has found herself living in:

I’m inside a hulking, poisoned, rotting monster that isn’t even aware it’s destroying itself with every footstep, it just keeps plodding along, causing misery and eating misery, instead of being put down in mercy.

They’ve given up empathy. They’ve given up sentiment, fond thoughts of the little things that make life worth living, that make it special and wondrous and joyful.

When a ruler gives up on empathy and sentiment, it is a sign of desperation. It means they’re paring away emotion in favor of efficiency and numbers and a twisted fantasy of a better life without the joys and burdens of caring about something outside of themselves. Contempt for kindness and generosity is the surest sign there is that someone has nothing else left to them but a horrible emptiness much worse than weakness.

And the dying monster plods along, unaware it’s rotting.

And, ultimately, Baron Valdemar decides this version of America isn’t worth saving; it can only be toppled and left behind.

Lackey was showing her teeth in Closer to the Chest and Eye Spy, but Beyond is where she bites.

It may be her finest work.

Leave a Reply